History of the Desert Peaks Section

An overview of our legacy

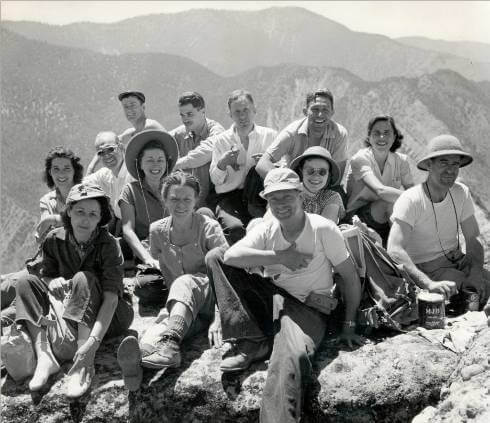

To better understand the foundation of the Desert Peaks Section and that elusive “list” many of us strive to complete, the following testimonies provide an informative overview of these topics. It’s basically presented here in the form of articles written by two long-time DPS members, John Robinson and Bill T. Russell. In his work, John Robinson supplies an account of the founding and early years of the Section as well as a short biography of its founder, Chester Versteeg. This article was printed in the October/November 1990 Desert Sage Newsletter No. 210 and is copied here in its entirety, providing the reader with a good understanding of the DPS’s formative years. In the second article, Bill T. Russell, former DPS Archivist/Historian, addresses the development of the ever-changing peaks list. This article was first published in the April/May 1991 Desert Sage Newsletter No. 213 and recalls the growth of the list from an initial seven peaks at the founding of the Section to the present-day ninety-seven described in this guide. It, like the preceding article, is presented here in its entirety to give DPS’ers a further glimpse into the Section’s history and Peaks List.

Chester Versteeg was a man of vibrant personality and boundless enthusiasm, well known to Southern California Sierra Clubbers for some four decades. Except in the summer when he was off tramping in the High Sierra, he seldom missed the Club’s Friday night dinners at Boos Brothers Cafeteria in downtown Los Angeles. Here, among friends in a genial atmosphere, Chester’s enthusiasm was infectious. Many a time, by the force of personality alone, he was the driving force behind Club projects and outings. And here, in the friendly surroundings of Boos Brothers, was the genesis of the Desert Peaks Section.

The idea of climbing desert peaks came to Chester while he was climbing in the Sierra Nevada in 1940. Gazing eastward from the Sierra crest, he noticed range after range of tawny mountains fading to the distant horizon. His curiosity was activated. What were these desert ranges like? Were they as devoid of life as they appeared? When snow closed the Sierra passes in the fall of 1940, Chester decided to find out.

His first desert ascent was New York Butte, a rounded, pinyon-clad summit across Owens Valley from Mount Whitney. Chester was delighted with what he found. The mountain was not barren at all. Its upper slopes were clad with pinyon pine and juniper. There was a spring of icy-cold water just below the crest. The view across Owens Valley at the snowy Sierra crest was breathtaking.

The Friday after his New York Butte climb, Chester was at Boos Brothers, talking up the idea of a climbing group specializing in ascending desert peaks. But his idea took a while to reach fruition. Louise Werner describes the birth pangs of the Section: “If there was any one quality that especially characterized Chester, it was enthusiasm. Out of his infectious enthusiasm was born the Desert Peaks Section. It did not, however, spring fullfledged,

like Minerva from the head of Zeus. Chester’s flame all but died under the soggy indifference he encountered every time he brought up the subject. It took a good deal of fanning and blowing before it caught a few individuals who went along, at first, mainly because Chester was such a persistent salesman. We can see him yet, before a crowd of Friday-nighters at Boos Brothers Cafeteria, trying to warm us up to the idea.”

Chester proposed that membership in the newly-formed group be attained by climbing seven peaks in the ranges east of Owens Valley: White Mountain, Waucoba Mountain, New York Butte, Cerro Gordo, Coso Peak, Maturango Peak and Telescope Peak.

On the weekend of November 15-16, 1941, the first scheduled activity of Chester’s new group was held: a climb of New York Butte led by Chester and Niles Werner. The Chapter schedule proclaimed in typical Versteegian prose, “Here is your opportunity to knock down one of the seven peaks required to make you eligible for the new Desert Peaks Section. New York Butte presents one of the grandest alpine views on the entire continent, the Sierra Crest from Olancha Peak clear to Mt. Tom.”

As fate would have it, momentous outside events intervened to place a temporary damper on the fledgling group. With World War II gas rationing, desert climbing activities were reduced to occasional forays by a handful of gas-sharing enthusiasts. But with the war’s end, all the pent-up energies of Chester and his band of desert peakers burst forth in renewed activity. In late 1945 the Desert Peaks Section was organized as a formal section of the Angeles Chapter. Chester declined the chairmanship, but did agree to serve on the management committee.

The steady growth of the Desert Peaks Section in the 1950’s was a source of pride to Chester. With the Section in capable hands, he turned to other projects. One of these was the Trojan Peak Club, which Chester organized among University of Southern California students and alumni in 1951.

Chester Versteeg, 76 years old, died in 1963. Besides the DPS, Chester’s legacies include the 250-odd Sierra Nevada peaks, passes, lakes and meadows he named. After his passing, at the urgency of Chester’s many friends, the United States Board on Geographic Names accepted the name “Mount Versteeg” for a majestic 13,470-foot summit on the Sierra crest near Mount Tyndall. Over the Labor Day weekend of 1965, I led a dedication climb of Mount Versteeg and placed a register on the summit containing a brief summary of Chester’s life and accomplishments.

– John Robinson

Following is the article written by Bill T. Russell which details the growth of the DPS Peaks list from conception to its present form.

The first table below gives data on each edition of the Peaks List as a stand alone document; the lists that were printed in Chapter Schedules in the 1950’s are based on these documents. The second table gives the date at which each of the present 97 peaks was added to the DPS Peaks List. It also has the dates for Cerro Gordo, Coso and Marble which were later deleted. The data for both tables was compiled from Angeles Chapter schedules, from the Southern Sierran which started publication in May 1946, from the DPS Newsletter, now THE DESERT SAGE, which started in March, 1950 and from DPS records including minutes of meetings.

In 1941, Chester Versteeg selected the seven peaks that comprised the initial “List of Qualifying Peaks”. Sierra Club members who “negotiated all seven peaks” could become members of the Section. The peaks are listed in the DPS paragraph in Schedule 109, Spring 1942 (see SAGE 212, page 37). The original membership roll has ten signatures of people who met this requirement, the first three are Chester Versteeg, Niles Werner and Freda Walbrecht. In early 1947, the change was made to require only six peaks for membership; bagging all seven earned the handsome, newly created emblem pin.

In mid 1947, Boundary and Charleston were added by the DPS Mountaineering Committee and, by Navy request, Coso and Maturango were removed. In early 1948 four more peaks were added and Coso and Maturango were reinstated, making a total of thirteen. Probably at this time, the emblem requirement was changed to seven peaks, including New York Butte, Telescope and White Mountain, which thereby became the initial emblem peaks.

In December 1948, the Mountaineering Committee added two peaks and, at the annual meeting in December 1949 the membership approved three more. The Annual meeting of January 11, 1952 dropped Cerro Gordo and replaced it with nearby Pleasant. The 1953 meeting defrocked White Mountain as an emblem peak because it now had a road to the summit, and elevated Montgomery and Rabbit. The emblem requirement was raised to nine peaks including the four emblem peaks.

From 1949, peaks were added or deleted by membership vote at the annual meetings or at business meetings. Until 1963, a quorum was 10 members and after that it was 10% of the membership. However, only six members attended the November 1960 annual meeting at Harwood Lodge when Old Woman Mountain was added. Mail ballots were used as early as 1965 for peak list changes but the requirement for mail balloting of all the members was not put into the bylaws until April 1973.

The annual meeting of December 7, 1956 delisted Coso and Maturango because of difficulty of access. Both peaks were added again to the list in 1961 but Coso was delisted for good in 1973. Marble was also delisted in 1973 because of the nearby new freeway. Two other peaks which came and went were Funeral, December 1957 to December 1959 and Searles, May 1959 to March 1960.

At a meeting in May 1959, Kofa (now Signal) was made an emblem peak. The number of peaks for the emblem was raised to fifteen including the five emblem peaks which were now New York Butte, Telescope, Montgomery, Rabbit and Kofa. In May 1960, Inyo replaced New York Butte as an emblem peak; the latter had become a possible drive up. In March 1966, El Picacho del Diablo, and in April 1973, Charleston Peak were made emblem peaks, but the requirement for the emblem stayed at fifteen peaks including five of the seven emblem peaks.

– Bill T. Russell